The new funding round pulled in cash from Nvidia, Google, Breakthrough Energy Ventures (Bill Gates' outfit), and nearly two dozen other punters. The money will be used to grease the company’s supply chains and butter up potential power buyers for its future reactors. This brings Commonwealth’s war chest to a staggering $3 billion, making it the richest fusion startup on the planet.

Chief executive and co-founder Bob Mumgaard said, “This round of capital isn't just about fusion just generally as a concept... It's about how do we go to make fusion into a commercial industrial endeavour.” So not just pipe dreams and plasma anymore, then.

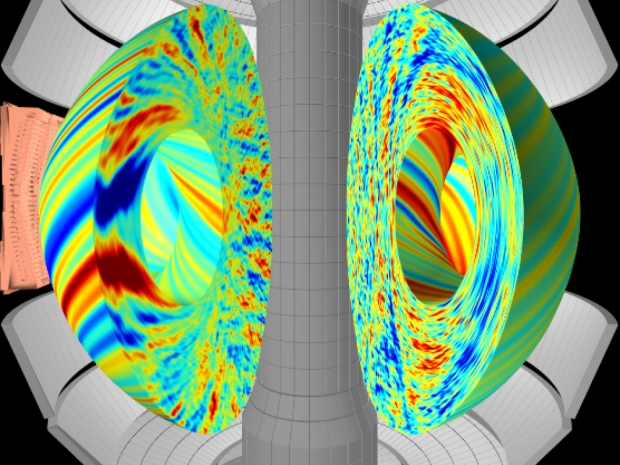

CFS is bolting together a prototype reactor called Sparc in a Boston suburb, which it hopes to flip the switch on sometime next year. The goal is to hit scientific breakeven by 2027, meaning the machine puts out more energy than it sucks in. That would be a first, and something fusion nerds have been promising since the 1950s.

Sparc won’t actually sell any power to the grid, but it’s a critical step for a full-on commercial power plant called Arc, which is set to break ground in Virginia as early as 2027. That is, assuming Sparc doesn’t go belly up or wander into some unexplored plasma hellscape.

Associate professor of physics at the College of William and Mary Saskia Mordijck said: “There are parts of the modelling and the physics that we don't yet understand. It's always an open question when you turn on a completely new device that it might go into plasma regimes we've never been into.”

Fusion has become the new darling of deep-pocketed backers thanks to recent advances in AI, simulation and computing, which let researchers test their science without blowing up lab gear. Investors in the latest round are throwing money at the dream that Sparc will work and that Arc will eventually spit out clean, grid-ready power.

Big Tech wants it up and running to sort out the power supply for their cloud and AI operations, which suck up rather a lot of juice. The US's power grid is rather primitive and in some places brown outs are common.

Even with this round, there’s not enough in the kitty to build Arc, which Mumgaard admits will “likely cost several billion dollars.”

“It's to have the receipts, know what these things cost,” he said, pointing out that Sparc is about building the business case for turning fusion into industry, not just a sci-fi fantasy.